According to Dr. Trerotola, an interventional radiologist at Penn Medicine, the study convincingly showed that “fibers made a huge difference in terms of acute occlusion compared to non-fibered coils”1 in the arterial vasculature.

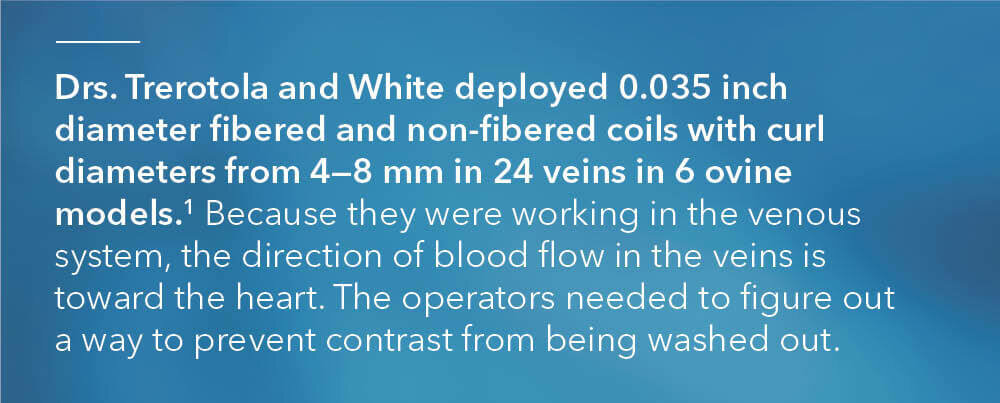

But this type of study had never been performed in the venous system. Dr. Trerotola and Dr. Sarah White, an interventional radiologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin, along with scientists at Cook Research Inc. (CRI) conducted another first-of-its-kind study: a direct, blinded, head-to-head comparison of fibered vs. non-fibered coils, but this time in a venous setting. In May 2023, the team published their results in theJournal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology in the article “Comparison of Fibered versus Nonfibered Coils for Venous Embolization in an Ovine Model.”

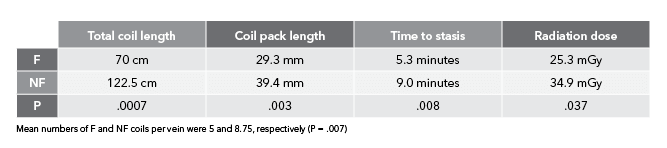

According to Ben Fisher, Cook Medical’s global product manager for embolization coils, “The arterial study was unique because it limited other variables except for fiber in order to focus solely on the performance of fibered vs. non-fibered coils. The venous study design matched the arterial study design in limiting the variables to fiber vs. no fiber. The venous study added some additional primary endpoints, which included testing speed to occlusion and measuring radiation dose.”

Scientists at CRI collaborated on-site with Drs. Trerotola and White to replicate a clinical scenario that had not been studied historically. CRI specializes in clinical research, non-clinical and pre-clinical testing, medical and scientific writing, and regulatory strategy.

CRI operates an in-house histology laboratory that utilizes new techniques to create histology slides and images for pathologists to read. In 2019, the lab developed a state-of-the-art process to create ultra-thin 5 µm (1/5,000th of an inch) slides using a hard plastic resin. While paraffin (wax) histology at this thickness is quite common, ultra-thin hard plastic histology is uncommon.

The plastic resin allows the specimen to include metal, such as from a coil or stent, so researchers can better interpret tissue changes over time. Both thick and thin sectioning are used to create images for studies.

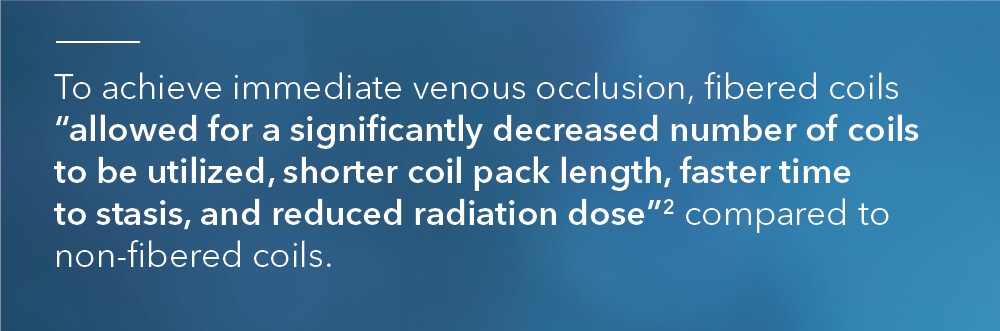

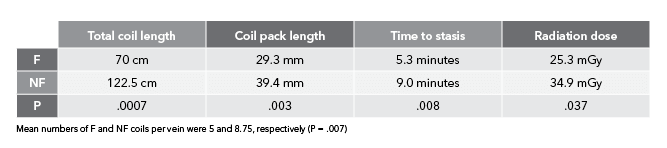

“In the arterial study, we didn’t explicitly look at parameters like time to occlusion and overall radiation dose. We only looked at number of coils needed to achieve occlusion,” Ben said. “We wanted to study those additional parameters this time around so we could draw more conclusions on bare metal vs. fibered coils. This way, when you’re looking at an acute setting, you can say with certainty that you’re going to need fewer coils, it’s going to take less time, and it’s going to use less radiation to achieve the clinical result of occlusion and embolization with fibered coils as compared to non-fibered coils.”

“On the venous side, you’re moving against the blood flow. So, when you inject contrast, it flows back toward the catheter rather than farther downstream into the vasculature, as with arteries,” Ben explained.

“When you place a coil, you’re basically trying to force contrast into the coil pack to see if the veins are going to occlude. It’s difficult in a normal clinical setting to say with 100% certainty whether a vein has occluded or not, just because of the way the contrast flows. So, we had to think of a way around this.”

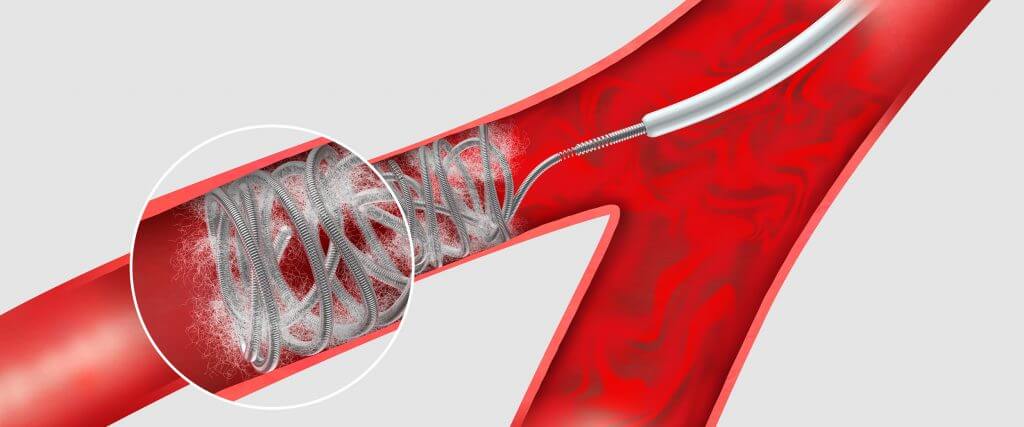

Drs. Trerotola and White found that solution. They incorporated a second catheter distal to the coil pack. When contrast was injected, it moved in the direction of the blood flow towards and through the coil pack. They were then able to determine if the coil pack was still open or if it had effectively shut off blood flow.

“Normally, the catheter is located proximal to the coil pack. We determined a second catheter was needed distal to the coil pack to inject contrast. This way, the blood flow could carry the contrast toward the coil pack to see if stasis was achieved. If contrast was moving through the coil pack, we added more coils,” Ben explained.

This is a novel technique that could have potential usage in future clinical settings to determine total occlusion.

“When we see in vivo results like this in studies, we hope the same benefits will be applicable to human patients,” said Remco van der Meel, the director of product management for Cook’s Interventional specialty. “We are constantly evaluating our Embolization portfolio, exploring cutting-edge technology, and gathering data to create new technology. Additionally, we want to understand how we could best support our customers in achieving the best possible outcomes for patients. This study helps us make data-based decisions on how to best meet the needs for effective embolization in a cost-efficient manner, while reducing exposure to ionizing radiation for both doctor and patient. These are key elements in today’s healthcare environment.”

References

- Trerotola SO, Pressler GA, Premanandan C. Nylon fibered versus non-fibered embolization coils: comparison in a swine model. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30(6):949–955.

- White SB, Wissing ER, Van Alstine WG, et al. Comparison of fibered versus nonfibered coils for venous embolization in an ovine model. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023;34(5):888–895.

Detach with precision.

The Retracta coil is a detachable .035 inch diameter coil that’s fully retractable¹ and based on platinum Nester® coil technology.

Using a screw mechanism, the Retracta coil remains firmly attached to the delivery wire until you detach it, even if you push the detachment zone out of the catheter. Under fluoroscopy, the change in radiopacity at the detachment zone tells you where the coil is, allowing you to inject contrast to confirm that the coil is correctly placed. If you need to reposition the coil, pull the coil back into the catheter and adjust its position. When you’re satisfied with the placement, simply detach the coil.

- The Retracta coil is fully retractable until it is detached from the delivery wire.

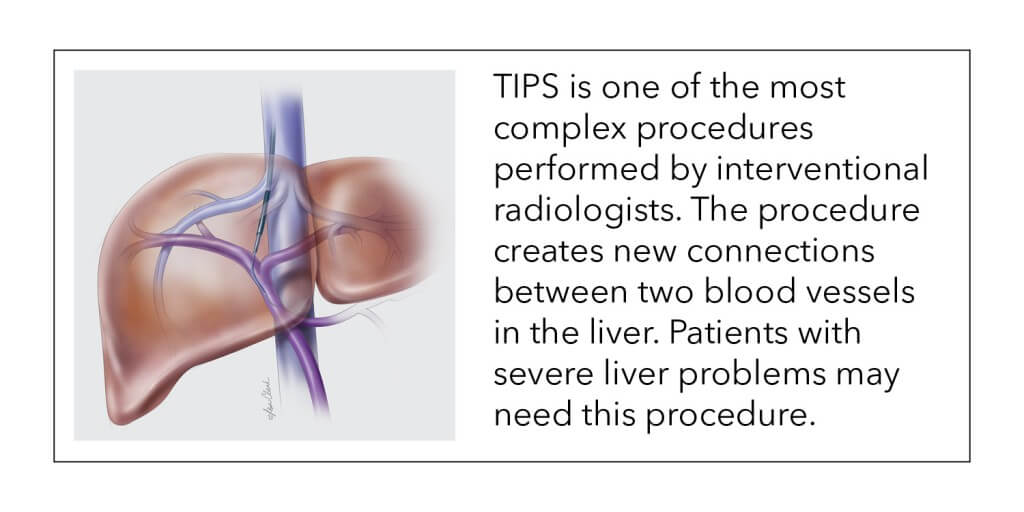

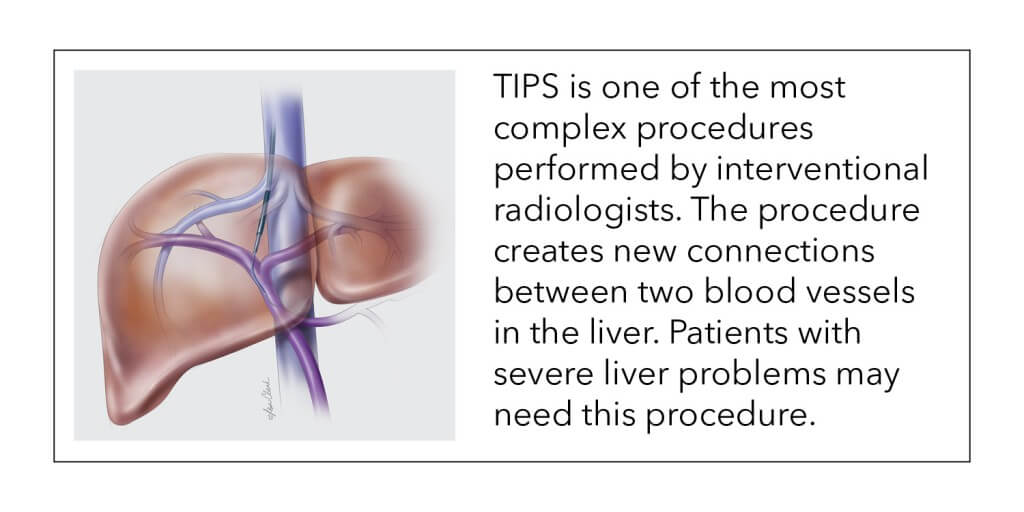

Dr. Josef Rösch, who pioneered important new medical techniques and interventional procedures, passed away early this year at the age of 91. Some of his innovations include the use of embolization to control gastrointestinal bleeding and the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure.

“Cook has had the pleasure and the wonderful opportunity to work with this great pioneer of interventional radiology. Josef’s kind demeanor and unyielding passion for improving patient care were truly inspirational and will be an example to all.”

—Rick Mellinger, vice president, global marketing, Cook Medical

Dr. Rösch began his career in Prague, Czech Republic, where he performed his first angiographic procedure in 1954. Modern angiography had begun only a year earlier in Sweden, when Dr. Sven Seldinger introduced percutaneous arteriography. (Read more about Dr. Seldinger.)

In a video presentation1, Dr. Rösch shared his memories of the early days of interventional radiology:

“My first angiographic technique in 1954 was transparietal splenoportography, which is visualizing the portal venous system, using contrast material injected directly into the spleen.”

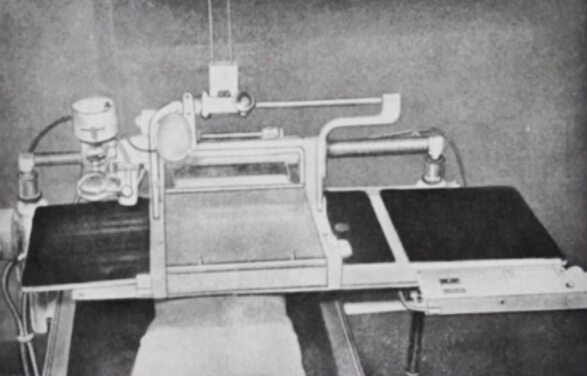

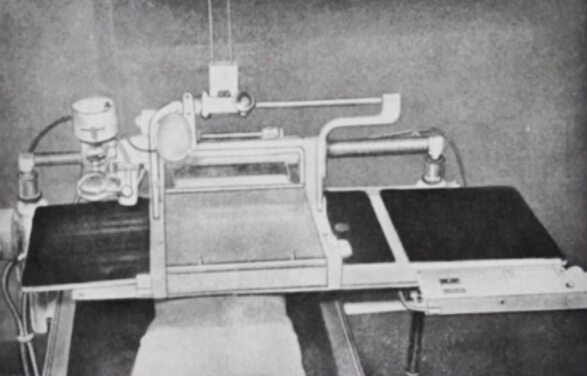

Dr. Rösch’s fluoroscopic table from 1954. Photo used by permission.

“Our angiographic equipment was quite primitive, a fluoroscopic table with X-ray slides that were manually pushed through. We practiced the procedure with the lights on and then did the actual procedure in the dark. Everything was simplified in 1957 when we received a dedicated angiographic room with a film changer.”

A historic partnership

During his 12 years in Prague, Dr. Rösch wrote two books, created two teaching movies, and wrote 60 scientific papers. The first American who asked for a reprint of Dr. Rösch’s paper on splenoportography was Dr. Charles T. Dotter, in 1959. Dr. Rösch sent the article to Dr. Dotter, and they became pen pals and colleagues, working together to create 27 scientific papers.

In 1963, Dr. Dotter visited Prague for a large worldwide conference and presented a talk entitled “Cardiac catheterization and angiographic techniques of the future,” which in the words of Dr. Rösch “planted the seeds of interventional radiology.” Read more about Dr. Dotter.

In 1965, Dr. Dotter invited Dr. Rösch to Oregon for a one-year fellowship at the University of Oregon Medical School in Portland. Dr. Rösch was then invited by UCLA to teach there on a fellowship. In 1969, Russia invaded Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) and Dr. Rösch and his family decided to stay in America, though they were sad to leave their homeland behind.

Dr. Dotter soon lured Dr. Rösch back to Portland, where he accepted a permanent position on the Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) faculty, and where he continued to work until his death.

Dr. Rösch was the first author or co-author of 495 published articles or book chapters. He was also an inventor and co-authored 12 patents. He was a respected and beloved mentor to young doctors throughout his life.

The creation of the Dotter Interventional Institute

In April, 1989, Bill Cook, founder of Cook Medical, spoke at the “Charles Dotter Memorial Days event” celebrating the life of Dr. Dotter, who died in 1985. During his speech, Cook announced Cook Medical’s significant financial contribution to OHSU to launch the Dotter Interventional Institute. The goals of the institute were to promote interventional education and research and to provide the highest-quality interventional treatment to patients.

Dr. Rösch became the founding director of the Dotter Institute, and his career at OHSU spanned more than 40 years. The Dotter Institute will hold a celebration of Dr. Rösch’s life on March 31, 2016. Read OHSU’s notice of Dr. Rösch’s passing.

Three Dotter Interventional Institute directors pose in front of a plaque depicting Dr. Charles T. Dotter: Dr. John Kaufman, the current director; Dr. Frederick Keller, past director; and Dr. Josef Rösch, founding director. Photo used by permission.

The Dotter Interventional Institute continues to further the scope of interventional treatment.

“Dr. Rösch was very patient, soft-spoken, and kind. He was able to find simple and elegant solutions to complex problems, and his name is on several of our products. He had the original vision of what the Dotter Institute could be, and he was the key person that drew people there to study.”

—Tom Osborne, senior vice president, intellectual property growth and development, Cook Medical

“Dr. Rösch was a true legend in the field of interventional radiology. His impact, both at OHSU and internationally, will not soon be forgotten.”

—John Kaufman, MD, MS, director, Dotter Institute and Frederick S. Keller Professor of Interventional Radiology, OHSU School of Medicine.2

Memorable sayings from Dr. Rösch

Dr. Frederick Keller, past director of the Dotter Institute, worked closely with Dr. Rösch and recalls some of his favorite Dr. Rösch sayings:

—Dr. Josef Rösch—

What is a TIPS procedure?

Dr. Frederick Keller and Dr. John Kaufman are paid consultants of Cook Medical.

*Portrait of Dr. Rösch by Keith Kline, Cook Medical

- Dr. Josef Rösch, “How it All Started: Personal Memories,” a video presentation for the IGI 50 meeting in Portland, OR, 2014.

- “In Memoriam: Josef Rösch, MD (1925-2016) https://www.ohsu.edu/xd/education/schools/school-of-medicine/news-and-events/memoriam-rosch.cfm