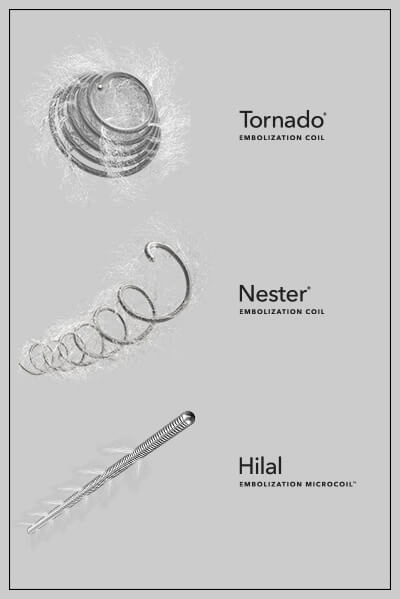

According to Dr. Trerotola, an interventional radiologist at Penn Medicine, the study convincingly showed that “fibers made a huge difference in terms of acute occlusion compared to non-fibered coils”1 in the arterial vasculature.

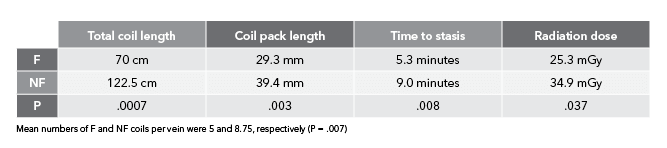

But this type of study had never been performed in the venous system. Dr. Trerotola and Dr. Sarah White, an interventional radiologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin, along with scientists at Cook Research Inc. (CRI) conducted another first-of-its-kind study: a direct, blinded, head-to-head comparison of fibered vs. non-fibered coils, but this time in a venous setting. In May 2023, the team published their results in theJournal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology in the article “Comparison of Fibered versus Nonfibered Coils for Venous Embolization in an Ovine Model.”

According to Ben Fisher, Cook Medical’s global product manager for embolization coils, “The arterial study was unique because it limited other variables except for fiber in order to focus solely on the performance of fibered vs. non-fibered coils. The venous study design matched the arterial study design in limiting the variables to fiber vs. no fiber. The venous study added some additional primary endpoints, which included testing speed to occlusion and measuring radiation dose.”

Scientists at CRI collaborated on-site with Drs. Trerotola and White to replicate a clinical scenario that had not been studied historically. CRI specializes in clinical research, non-clinical and pre-clinical testing, medical and scientific writing, and regulatory strategy.

CRI operates an in-house histology laboratory that utilizes new techniques to create histology slides and images for pathologists to read. In 2019, the lab developed a state-of-the-art process to create ultra-thin 5 µm (1/5,000th of an inch) slides using a hard plastic resin. While paraffin (wax) histology at this thickness is quite common, ultra-thin hard plastic histology is uncommon.

The plastic resin allows the specimen to include metal, such as from a coil or stent, so researchers can better interpret tissue changes over time. Both thick and thin sectioning are used to create images for studies.

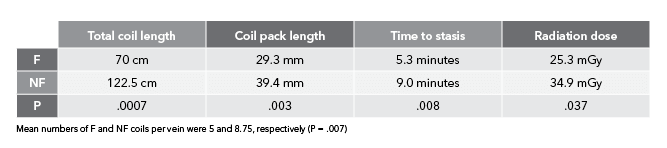

“In the arterial study, we didn’t explicitly look at parameters like time to occlusion and overall radiation dose. We only looked at number of coils needed to achieve occlusion,” Ben said. “We wanted to study those additional parameters this time around so we could draw more conclusions on bare metal vs. fibered coils. This way, when you’re looking at an acute setting, you can say with certainty that you’re going to need fewer coils, it’s going to take less time, and it’s going to use less radiation to achieve the clinical result of occlusion and embolization with fibered coils as compared to non-fibered coils.”

“On the venous side, you’re moving against the blood flow. So, when you inject contrast, it flows back toward the catheter rather than farther downstream into the vasculature, as with arteries,” Ben explained.

“When you place a coil, you’re basically trying to force contrast into the coil pack to see if the veins are going to occlude. It’s difficult in a normal clinical setting to say with 100% certainty whether a vein has occluded or not, just because of the way the contrast flows. So, we had to think of a way around this.”

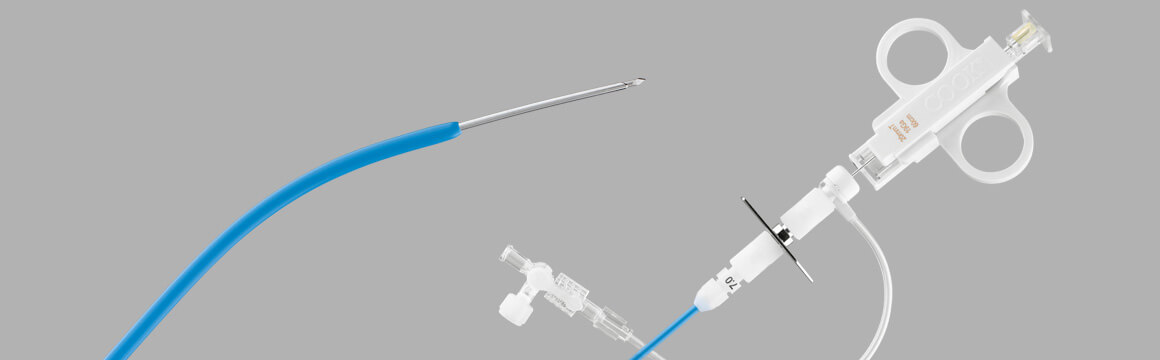

Drs. Trerotola and White found that solution. They incorporated a second catheter distal to the coil pack. When contrast was injected, it moved in the direction of the blood flow towards and through the coil pack. They were then able to determine if the coil pack was still open or if it had effectively shut off blood flow.

“Normally, the catheter is located proximal to the coil pack. We determined a second catheter was needed distal to the coil pack to inject contrast. This way, the blood flow could carry the contrast toward the coil pack to see if stasis was achieved. If contrast was moving through the coil pack, we added more coils,” Ben explained.

This is a novel technique that could have potential usage in future clinical settings to determine total occlusion.

“When we see in vivo results like this in studies, we hope the same benefits will be applicable to human patients,” said Remco van der Meel, the director of product management for Cook’s Interventional specialty. “We are constantly evaluating our Embolization portfolio, exploring cutting-edge technology, and gathering data to create new technology. Additionally, we want to understand how we could best support our customers in achieving the best possible outcomes for patients. This study helps us make data-based decisions on how to best meet the needs for effective embolization in a cost-efficient manner, while reducing exposure to ionizing radiation for both doctor and patient. These are key elements in today’s healthcare environment.”

References

- Trerotola SO, Pressler GA, Premanandan C. Nylon fibered versus non-fibered embolization coils: comparison in a swine model. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30(6):949–955.

- White SB, Wissing ER, Van Alstine WG, et al. Comparison of fibered versus nonfibered coils for venous embolization in an ovine model. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023;34(5):888–895.

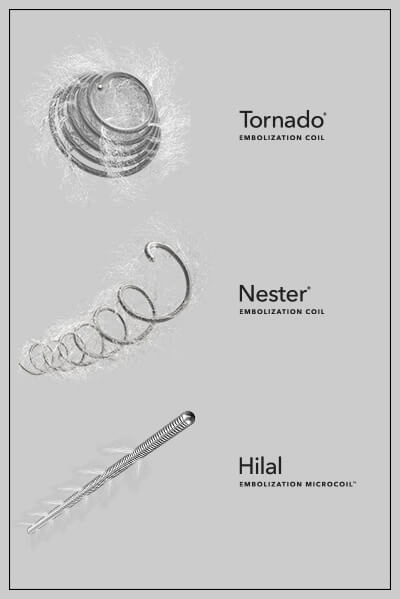

According to “Nylon fibered versus non-fibered embolization coils: comparison in a swine model,” an animal study authored by interventional radiologist Dr. Scott Trerotola, from the University of Pennsylvania, embolization coils with nylon fibers allow significantly fewer embolization coils to achieve acute occlusion of arteries compared to bare metal coils.

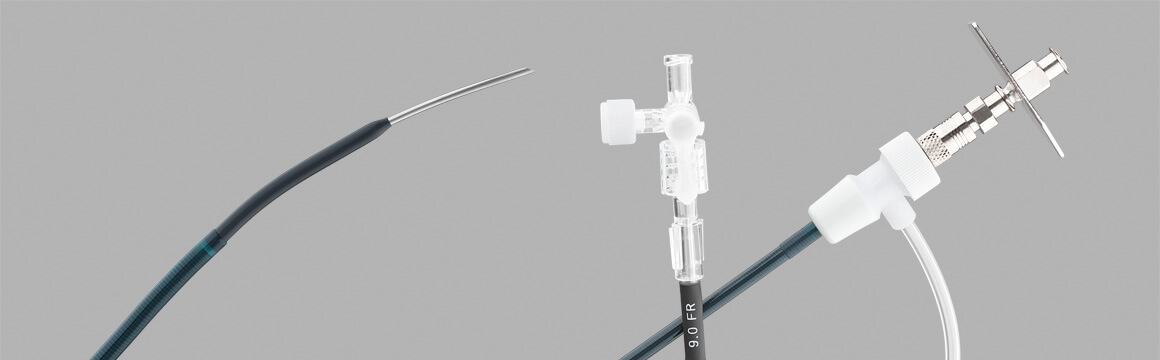

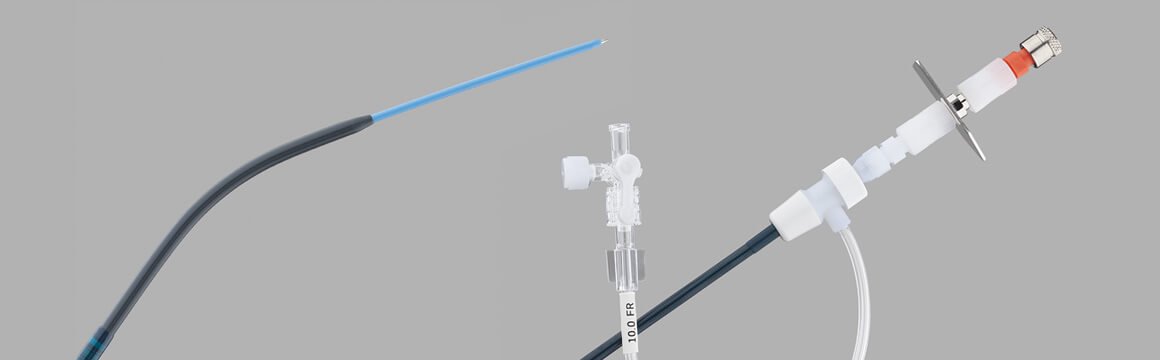

The purpose of this study was to determine whether nylon fibers improve the performance of platinum embolization coils in porcine arteries. The study tested the efficacy of platinum embolization coils, with and without nylon fibers, in the hindlimbs of six juvenile pigs. A total of 24 coils were used—12 with fibers and 12 without fibers. Specifically, the study looked at the number of coils needed to achieve vessel occlusion and the durability of occlusion at 1 and 3 months.

The study found that fewer fibered coils were needed to achieve acute occlusion compared to bare metal coils. A mean of 3.2 bare metal coils was required to achieve occlusion, while a mean of only 1.3 fibered coils was necessary to occlude the targeted vessels. Both fibered and non-fibered coils showed similar rates of recanalization at follow-up.

The study, which was randomized and blinded and utilized a single operator to eliminate experimental bias, is among the first to provide strong evidence supporting what clinicians have long observed: that fibers enhance thrombogenicity. Although some early studies suggested that fibers benefit occlusion, the coil and fiber material used in those studies differs from material in devices used today. The present study compares modern platinum coils both with fibers and without and was designed to limit variables to the greatest extent possible.

The study does provide strong evidence that the incorporation of nylon fibers in metallic embolization coils has been shown to significantly reduce the number of coils required to occlude peripheral arteries. Based on the results of the study, in the setting where acute occlusion is important, it would appear that fibers have an advantage over non-fibered coils.

To read the details of this statistically significant, peer-reviewed in-vivo study published in JVIR, go here.

Dr. Trerotola is a paid consultant of Cook Medical.

IR-D48664-EN

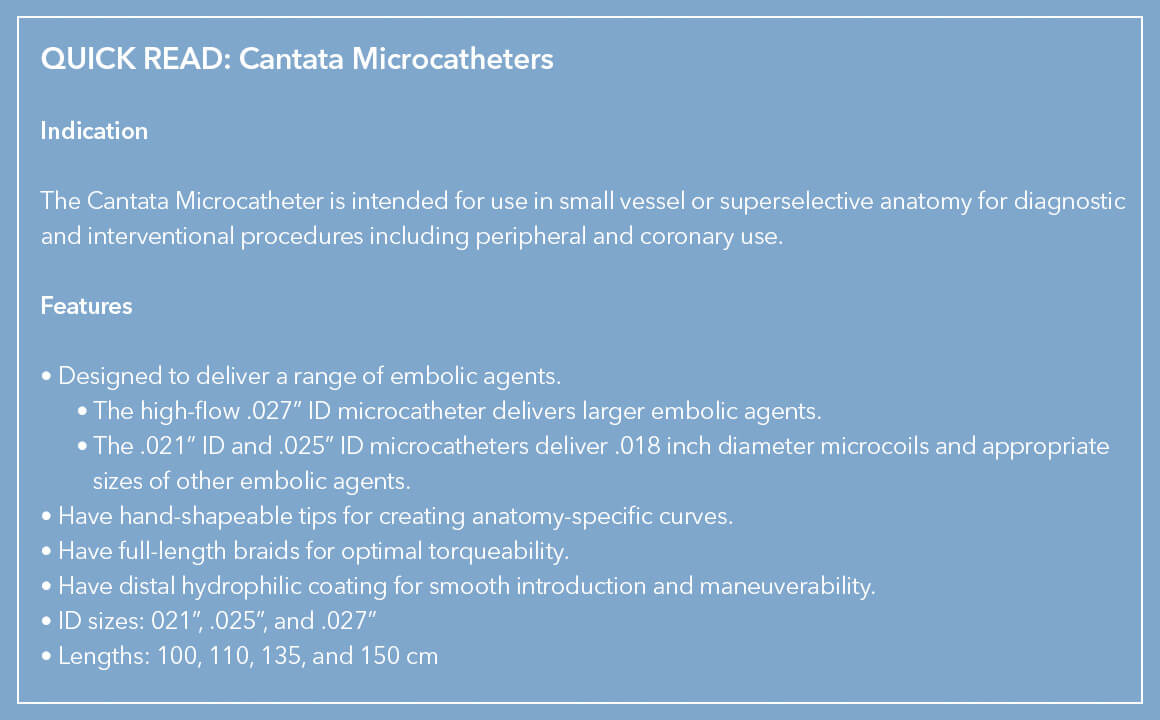

Blood may be the essence of life, but there are times when a physician needs to stop or redirect blood flow to treat a patient or even save his or her life. Using minimally invasive interventional techniques–an alternative to open surgery–embolic agents can be delivered through a microcatheter and implanted in tiny blood vessels to cut off blood supply to a particular area of the body. “Coils and particles stop blood flow by creating an occlusion,” said Clint Merkel, global program manager responsible for the Cantata Microcatheter line.

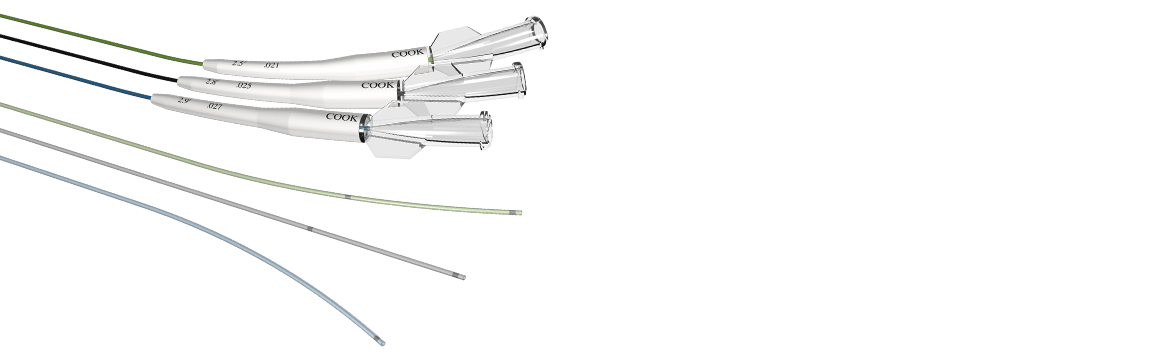

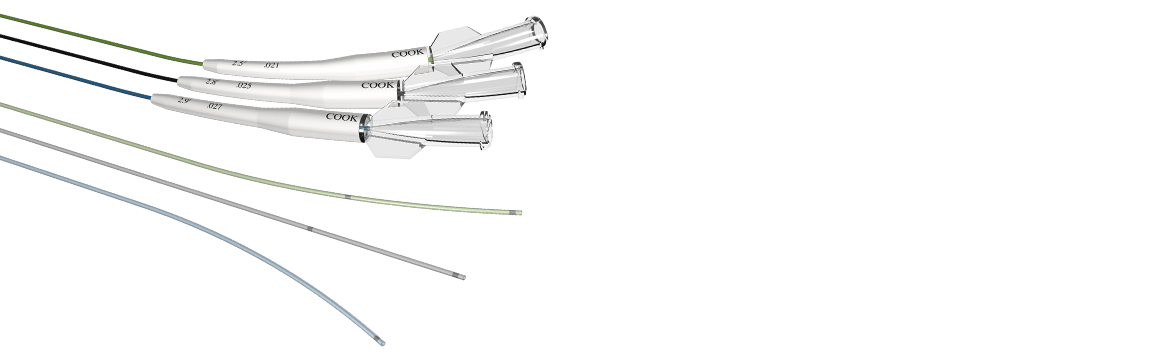

Between them, Cook’s family of three Cantata Microcatheters are designed to deliver particles such as non-spherical PVA Foam Embolization Particles and microsphere, embolization coils, and other embolic agents, including glue or alcohol fluid, to very small vessels in the peripheral vasculature. The high-flow .027” inner diameter (ID) Cantata Microcatheter delivers relatively larger embolic agents to target anatomy while the .021” ID and .025” ID Cantata Microcatheters deliver .018” diameter microcoils and appropriate sizes of other embolic agents.

Between them, Cook’s family of three Cantata Microcatheters are designed to deliver particles such as non-spherical PVA Foam Embolization Particles and microsphere, embolization coils, and other embolic agents, including glue or alcohol fluid, to very small vessels in the peripheral vasculature. The high-flow .027” inner diameter (ID) Cantata Microcatheter delivers relatively larger embolic agents to target anatomy while the .021” ID and .025” ID Cantata Microcatheters deliver .018” diameter microcoils and appropriate sizes of other embolic agents.

Particles can be used where coils are too large, or where there are networks of small blood vessels feeding a tumor, fibroid, or arteriovenous malformations. “Because of their small size, particles can reach deeper into smaller arteries and wedge themselves there to stop the blood supply,” Clint explained. “Depending on the particle size needed, there is a Cantata Microcatheter to help deliver the agent.”

Each of the Cantata Microcatheters has a maximum particle size limit: 500 μm for the 2.5 Fr superselective Cantata, 700 μm for the 2.8 Fr superselective Cantata, and 1,000 μm for the 2.9 Fr high-flow Cantata.

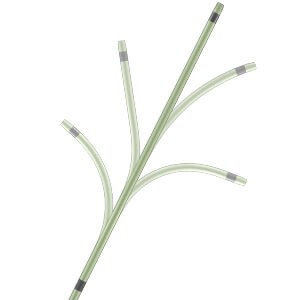

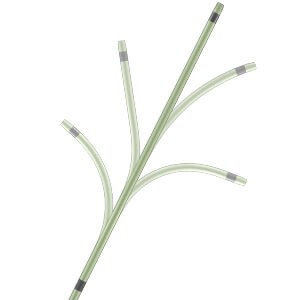

A unique feature of all Cantata Microcatheters is that their tips can be shaped by hand. This gives physicians several options for optimal access to difficult anatomy. “Cantata is designed to navigate through tortuous anatomy,” said Albert de Troije, EMEA area program manager for Cook’s embolization devices. “You can shape the tip by hand to create curves that complement specific anatomy. It doesn’t require heat or steam. Cook has the only device on the market like this because of the proprietary braid that runs the length of the microcatheter.”

A unique feature of all Cantata Microcatheters is that their tips can be shaped by hand. This gives physicians several options for optimal access to difficult anatomy. “Cantata is designed to navigate through tortuous anatomy,” said Albert de Troije, EMEA area program manager for Cook’s embolization devices. “You can shape the tip by hand to create curves that complement specific anatomy. It doesn’t require heat or steam. Cook has the only device on the market like this because of the proprietary braid that runs the length of the microcatheter.”

The hand-shapable feature of Cantata Microcatheters enable physicians to make anatomy-specific curves.

Besides the unique hand-shapability of the braid tip, the microcatheter design also provides control, torquability, and kink resistance. To enable optimal trackability, Cantata’s full-length stainless-steel braid has five transition zones that provide a distinct yet seamless transition from hub to tip. The braid also has a distal hydrophilic coating to ensure smooth introduction and maneuverability through arteries and veins.

To view the flow rate chart of different infusion mediums in the three Cantata Microcatheters, as well as ordering information, go here.

IR-D67689-EN

By using what is at hand, adapting existing tools to new uses, and conceiving of entirely new solutions, innovative Cook product-development staff and brilliant physicians and technicians have collaborated to develop, evaluate, and perfect interventional devices for over 50 years.

By using what is at hand, adapting existing tools to new uses, and conceiving of entirely new solutions, innovative Cook product-development staff and brilliant physicians and technicians have collaborated to develop, evaluate, and perfect interventional devices for over 50 years.

This solution-seeking synergy is seen in the evolution of Cook’s liver access and biopsy sets, referred to as the RING, the RUPS, and the LABS sets. These sets are still being used in interventional procedures 20 years after they first came to market. To find out more about the role they played in the advancement of the field of interventional radiology, we talked with some of the key innovators, both inside and outside of Cook, who collaborated to develop these sets: Dr. Ernest Ring, now retired from UCSF; Barry Uchida, X-ray technician and researcher at OHSU’s Dotter Institute; Joe Roberts, Cook VP of corporate development; and Ray Leonard, Cook global corporate development manager.

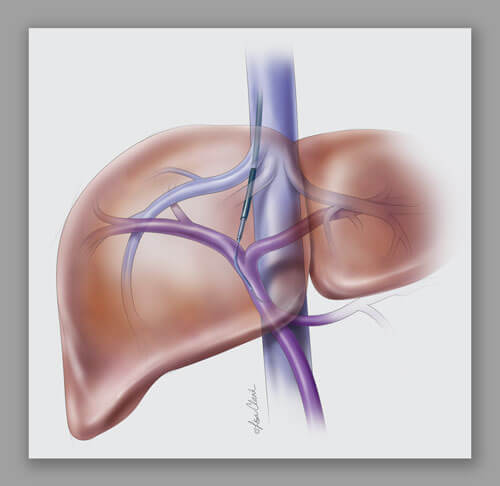

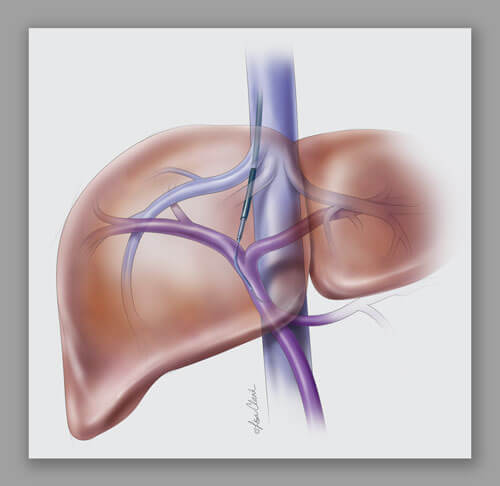

Both the Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING) and the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS) are often used during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. The sets’ components are used to access the liver using a transjugular approach and then create a pathway through the liver to connect the portal and hepatic systems, laying the groundwork for the placement of a stent.* Similarly, the Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS) uses a transjugular approach to take a biopsy of the liver.

Both the Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING) and the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS) are often used during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. The sets’ components are used to access the liver using a transjugular approach and then create a pathway through the liver to connect the portal and hepatic systems, laying the groundwork for the placement of a stent.* Similarly, the Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS) uses a transjugular approach to take a biopsy of the liver.

Dr. Ernie Ring: “Control was critical”

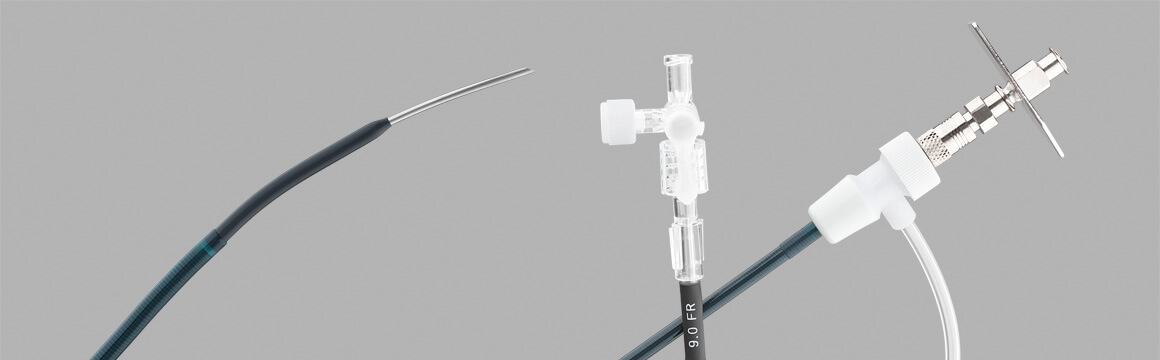

Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING), launched in 1991

Dr. Ring worked with Cook managers and engineers, particularly Joe Roberts, to find new ways to use an image-guided needle for liver biopsy and to use drainage catheters for percutaneous drainage of the biliary tree. Dr. Ring and other clinicians made use of the components from the Colapinto Transjugular Cholangiography and Biopsy Set** for accessing the liver. We asked Dr. Ring how he conceived of the idea for the RING set.

“I had been doing the same kind of procedure, using a long needle and going in from the side using a transhepatic approach. It occurred to me that I could make the procedure more efficient by going in from the top using a transjugular approach. I used what I had on the shelf, which was a Colapinto needle, invented by the late Dr. Ronald F. Colapinto of Toronto, and an Amplatz wire. The Colapinto was the right length, and the curve at its tip allowed it to be turned anteriorly. In the early days, if I needed anything, I’d just call Cook and they would build it for me.”

“Clinically, the big advantage of the RING is that it gives you the authority to redirect the needle,” continues Ring. “Once you get in, then it becomes a stiffening rod over which the sheath can advance. Some diseased livers are very hard but the RING set makes advancing a balloon* possible.”

“Scaling up from a 5 Fr system to a 9 or 10 Fr sheath was an easy adjustment that enabled a balloon* or stent* to pass through. Also, the Colapinto needle worked well because it is a hollow biopsy needle. The hollow needle created a passage through the liver and allowed you to check blood flow.”

Barry Uchida and Josef Rösch: innovating for physician preference

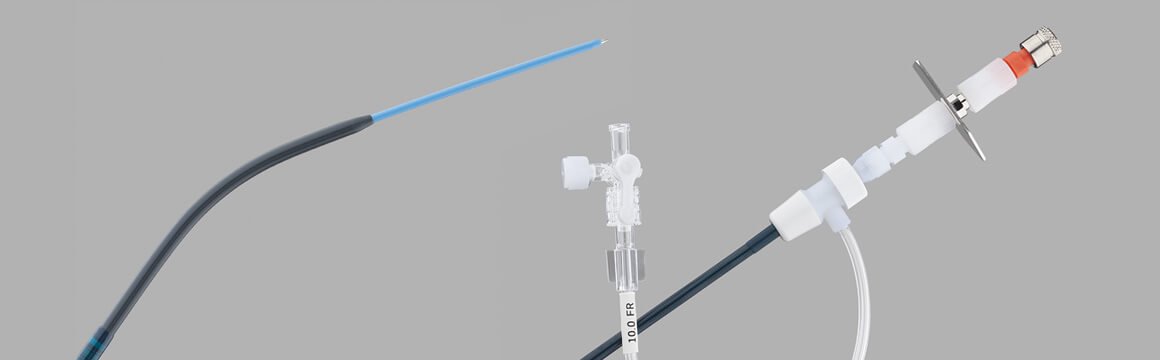

Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS), launched in 1992

Barry Uchida, a former X-ray technician who later became a researcher at the Dotter Institute, was deeply involved in the development of the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set. “We started developing the RUPS in 1988, when pioneers Charles Dotter and Josef Rösch were using the Colapinto needle to access the bile ducts for cholangiography. Dr. Rösch deserves credit for giving me the opportunity to develop ideas and for guiding me during the process. He was not only my boss, he was my partner and a true pioneer.” (Read our tribute to the late Dr. Rösch.)

Explains Uchida, “The RUPS overcame a clinical challenge for us because the set’s 14 gage cannula is more flexible compared to the Ring set. The RUPS also provides access without the frequent exchanges of multiple wire guides and catheters.”

Dr. Fred Keller, who was chief of the Dotter Institute then, began using the RUPS around 1993. Uchida says that Dr. Keller liked the RUPS because the puncture needle was smaller than the RING set needle. He also liked the fact that, as with the RING set, the catheters and dilators are all together in one set, and it is easier to place commonly used stents* through the 10 Fr Flexor® sheath.

Ray Leonard’s resourcefulness

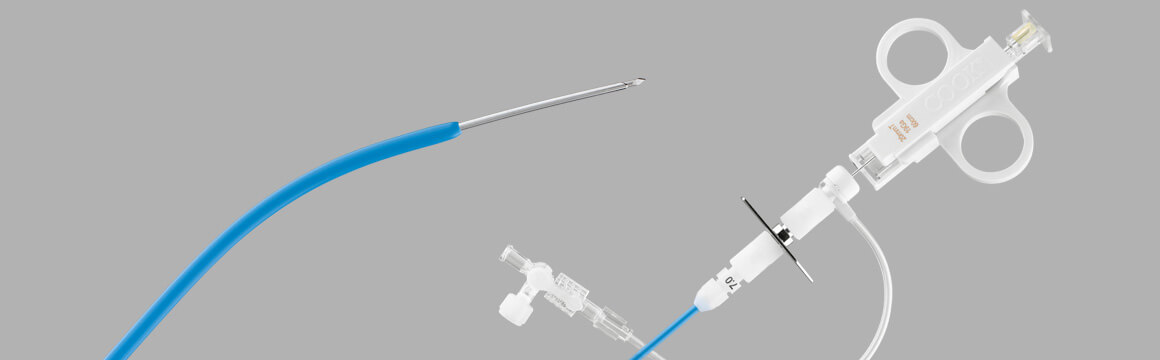

Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS), launched in 1994

Since Cook already had an inventory of soft tissue biopsy needles, and now had devices to access the liver, it only required one more step to provide a solution for gathering liver biopsies. Ray Leonard recalls, “I had the idea to pull the RUPS-100 set from stock and run the 18 gage Quick-Core® needles inside of them. Inside of the cannula the needle bound and grated during advancement, but the spring still fired. After further refining the idea, I sent the idea off to Hans Timmerman at the Dotter Institute to see if the concept worked. It did.”

Ray and his colleagues then worked with staff at the Dotter Institute and other institutions to evaluate the prototype LABS product. “Dr. Ernie Ring was one of the approximately seven clinicians who received clinical prototypes from Cook. Each evaluator gave us valuable input, including feedback from their pathologists. I remember sending each evaluator a thank you letter, attached to a data sheet showing the finished LABS product, to recognize them for their input,” adds Ray. A short time later, the LABS was launched as a transjugular liver biopsy solution.

RING versus RUPS: which would you prefer?

While the RUPS and RING accomplish the same goal of access to the liver, physicians today choose the set that best fits their technique. For physicians wanting to learn how to use these Cook devices, training courses involving didactic presentations, table top models, and hands-on animal labs are offered through Cook’s Vista® Education and Training Program at vista.cookmedical.com.

To learn more about each set, click on the links below to view our RING, RUPS, and LABS instructions for use, animations, and illustrated guides:

RING product page

RUPS product page

LABS product page

* Balloons and stents are not included in the RUPS or RING liver access sets.

** Now discontinued.

IR-D45651-EN

Between them, Cook’s family of three Cantata Microcatheters are designed to deliver particles such as non-spherical PVA Foam Embolization Particles and microsphere, embolization coils, and other embolic agents, including glue or alcohol fluid, to very small vessels in the peripheral vasculature. The high-flow .027” inner diameter (ID) Cantata Microcatheter delivers relatively larger embolic agents to target anatomy while the .021” ID and .025” ID Cantata Microcatheters deliver .018” diameter microcoils and appropriate sizes of other embolic agents.

Between them, Cook’s family of three Cantata Microcatheters are designed to deliver particles such as non-spherical PVA Foam Embolization Particles and microsphere, embolization coils, and other embolic agents, including glue or alcohol fluid, to very small vessels in the peripheral vasculature. The high-flow .027” inner diameter (ID) Cantata Microcatheter delivers relatively larger embolic agents to target anatomy while the .021” ID and .025” ID Cantata Microcatheters deliver .018” diameter microcoils and appropriate sizes of other embolic agents. A unique feature of all Cantata Microcatheters is that their tips can be shaped by hand. This gives physicians several options for optimal access to difficult anatomy. “Cantata is designed to navigate through tortuous anatomy,” said Albert de Troije, EMEA area program manager for Cook’s embolization devices. “You can shape the tip by hand to create curves that complement specific anatomy. It doesn’t require heat or steam. Cook has the only device on the market like this because of the proprietary braid that runs the length of the microcatheter.”

A unique feature of all Cantata Microcatheters is that their tips can be shaped by hand. This gives physicians several options for optimal access to difficult anatomy. “Cantata is designed to navigate through tortuous anatomy,” said Albert de Troije, EMEA area program manager for Cook’s embolization devices. “You can shape the tip by hand to create curves that complement specific anatomy. It doesn’t require heat or steam. Cook has the only device on the market like this because of the proprietary braid that runs the length of the microcatheter.”

By using what is at hand, adapting existing tools to new uses, and conceiving of entirely new solutions, innovative Cook product-development staff and brilliant physicians and technicians have collaborated to develop, evaluate, and perfect interventional devices for over 50 years.

By using what is at hand, adapting existing tools to new uses, and conceiving of entirely new solutions, innovative Cook product-development staff and brilliant physicians and technicians have collaborated to develop, evaluate, and perfect interventional devices for over 50 years. Both the Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING) and the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS) are often used during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. The sets’ components are used to access the liver using a transjugular approach and then create a pathway through the liver to connect the portal and hepatic systems, laying the groundwork for the placement of a stent.* Similarly, the Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS) uses a transjugular approach to take a biopsy of the liver.

Both the Ring Transjugular Intrahepatic Access Set (RING) and the Rösch-Uchida Transjugular Liver Access Set (RUPS) are often used during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. The sets’ components are used to access the liver using a transjugular approach and then create a pathway through the liver to connect the portal and hepatic systems, laying the groundwork for the placement of a stent.* Similarly, the Liver Access and Biopsy Set (LABS) uses a transjugular approach to take a biopsy of the liver.